Our religions have proclaimed from the very beginning that each human individual is to be regarded as a spark of the Divine. Tat tvam asi, thou art That, is the teaching of the Upanishads. The Buddhists declare that each individual has in him a spark of the Divine and could become a Bodhisattva. These proclamations by themselves are not enough. So long as these principles are merely clauses in the Constitution, and not functioning realities in the daily life of the people, we are far from the ideals which we have set before ourselves. Minds and hearts of the people require to be altered. We must strive to become democratic, not merely in the political sense of the term, but also in the social and economic sense. It is essential to bring about this democratic change, this democratic temper, this kind of outlook, by a proper study of the humanities, including philosophy and religion.

There is a great verse which says that in this poison tree of samsara are two fruits of incomparable value. They are the enjoyment of great books and the company of good souls. If you want to absorb the fruits of great literature, well, you must read them; read them not as we do cricket stories, but read them with concentration.

Our generation in its rapid travel has not achieved the habit of reading the great books and lost the habit of being influenced by the great classics of our country. If the principles of democracy in our Constitution are to become habits of mind and patterns of behaviour, principles which change the very character of the individual and the nature of the society, it can be done only by the study of great literature, of philosophy and religion. That is why, even though our country needs great scientists, great technologists, great engineers, we should not neglect to make them humanists. Science and technology are not all.

We must note the famous statement that, merely by becoming literate without the development of compassion we become demoniac. So no university can regard itself as a true university unless it sends out young men and women who are not only learned but whose hearts are full of compassion for suffering humanity. Unless that is there, the university education must be regarded as incomplete.

I have been a teacher for nearly all my adult life, for over forty years I have lived with students and it hurts me very deeply when I find that the precious years during which a student has to live in the university are wasted by some of them. I do not say by all of them.

Teachers and students form a family and in a family you cannot have the spirit of a trade union. Such a thing should be inconceivable in a university. University life is a co-operative enterprise between teachers and students and I do hope that the students will not do a disservice to themselves by resorting to activities which are antisocial in character.

Character is destiny. Character is that on which the destiny of a nation is built. One cannot have a great nation with men of small character. If we want to build a great nation, we must try to train a large number of young men and women who have character. We must have young men and women who look upon others as the living images of themselves, as our Sastras have so often declared. But whether in public life or in student life, we cannot reach great heights if we are lacking in character. We cannot climb the mountain when the very ground at our feet is crumbling.

When the very basis of our structure is shaky, how can we reach the heights which we have set before ourselves? We must all have humility. Here is a country which we are interested in building up. For whatever service we take up, we should not care for what we receive. We should know how much we can put into that service. That should be the principle which should animate our young men and women.

We are living through one of the great revolutionary periods in human history. The revolutionary efforts spread over several centuries in other parts of the world are concentrated in a short span of time in our country. We are facing a many-sided challenge, political and economic, social and cultural. Education is the means by which youth is trained to serve the cause of drastic social and economic changes. Nations become back-numbers if they do not reckon with the developments of the age.

The industrial growth of our country requires a large number of scientists, technicians and engineers. The rush in our universities for courses in science and technology is natural. Men trained in these practical courses help to increase productivity, agricultural and industrial. They also hope to find employment easily. To help the students to earn a living is one of the functions of education, arthakari ca vidya.

I do not believe that scientific and technological studies are devoid of moral values. Science is both knowledge and power. It has interest as well as utility. It is illuminating as well as fruitful. It demands disciplined devotion to the pursuit of truth. It develops in its votaries an attitude of tolerance, open-mindedness, freedom from prejudice and hospitality to new ideas. Science reveals to us the inexhaustible richness of the world, its unexpectedness, its wonder.

Nevertheless, these qualities are developed by science incidentally and not immediately. It does not directly deal with the non-intellectual aspects of human nature. Economic man who produces and consumes, the intellectual man, the scientific man is not the whole man.

The disproportionate emphasis on science and technology has been causing concern to thinking men all over the world. The great crimes against civilization are committed not by the primitive and the uneducated but by the highly educated and the so-called civilised. One recalls the saying that the most civilised State is no further from barbarism than the most polished steel is from rust.

Scientists have now found means by which human life can be wiped off the surface of this planet. Of the many problems that now face the leaders of the world, none is of graver consequence than the problem of saving the human race from extinction. Struggling as we are with the fateful horizons of an atomic age, the achievements of science have induced in our minds a mood of despair making us feel homeless exiles caught in a blind machine. We are standing on the edge of an abyss or perhaps even sliding towards it.

Any satisfactory system of education should aim at a balanced growth of the individual and insist on both knowledge and wisdom, jnanam vijnana-sahitam. It should not only train the intellect but bring grace into the heart of man. Wisdom is more easily gained through the study of literature, philosophy, religion. They interpret the higher laws of the universe. If we do not have a general philosophy or attitude of life, our minds will be confused, and we will suffer from greed, pusillanimity, anxiety and defeatism. Mental slums are more dangerous to mankind than material slums.

Independent thinking is not encouraged in our world today. When we see a film we think very fast to keep up with rapid changes of scene and action. This rapidity which the film gives its audiences and demands from them has its own effect on the mental development. If we are to be freed from the debilitating effect and the nervous strain of modern life, if we are to be saved from the assaults which beat so insistently on us from the screen and the radio, from the yellow press and demagogy, defences are to be built in the minds of men, enduring interests are to be implanted in them.

We must learn to read great classics which deal with really important questions affecting the life and destiny of the human race. We must think for ourselves about these great matters but thinking for oneself does not mean thinking in a vacuum, unaided, all alone. We need help from others, living or dead.

We need help from the great of all ages, the poets, ‘the unacknowledged legislators of the world’, the philosophers, the creative thinkers, the artists. Whereas in sciences we can be helped only by the contemporaries, in the humanities, help comes from the very great, to whatever age and race they may belong.

At the deepest levels of existence, in the intimations of the nature of the Supreme, and the economy of the universe, in the insights into the power and powerlessness of man, the changing scene of history has its focus. The events of history reflect the events in the souls of men.

If this country has survived all the changes and chances it has passed through, it is because of certain habits of mind and conviction which our people, whatever their race or religion may be, share and would not surrender. The central truth is that there is an intimate connection between the mind of man and the moving spirit of the universe. We can realize it through the practice of self-control and the exercise of compassion. These principles have remained the framework into which were fitted lessons from the different religions that have found place in this country.

Our history is not modern. It is like a great river with its source back in silence. Many ages, many races, many religions have worked at it. It is all in our bloodstream.

The more Indian culture changes, the more it remains the same. The power of the Indian spirit has sustained us through difficult times. It will sustain us in the future if we believe in ourselves.

It is the intangibles that give a nation its character and its vitality. They may seem unimportant or even irrelevant under the pressure of daily life. Our capacity for survival in spite of perils from outside matched only by our own internal feuds and dissensions is due to our persistent adherence to this spirit. If our young men are to live more abundantly, they should enter more fully into the experience and ideals of the race, they should be inspired in their minds and hearts by the great ideas enshrined in our culture….

Our future destiny as a nation depends on our spiritual strength rather than upon our material wealth: nayam atma balahinena labhyah. The goal of perfection cannot be achieved by the weak, not the weak in body, but the weak in spirit, atmanistha-janita-viryahinena. The greatest asset of a nation is the spirit of its people. If we break the spirit of a people, we imperil their future; if we develop the power of spirit, our future will be bright.

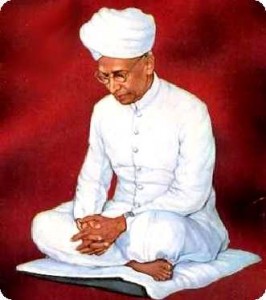

S. Radhakrishnan

(From Convocation Address delivered at Delhi University on December 5, 1953.)