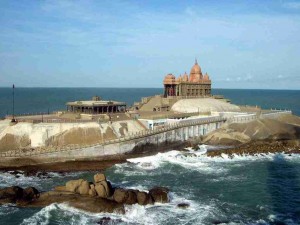

One early dawn in March I swam off Kanyakumari just as the great Swami had done back in 1892. The sea was turbulent and shark-infested as it had been for the Swami. But I am young and as a citizen I am classified as an unemployed graduate engineer, a fact which may or may not be relevant but which I mention because it comes to my mind. So, I crossed the turbulent, shark-infested waters and took position and began my wait for the sunrise and I looked back at the great continent of India which is also known as Bharat and I said to myself here I am, an unemployed graduate engineer on this rock and here is this great continent and, what about it. I was not thinking about my being an unemployed graduate engineer. As I said, that is only my classification, like saying I am a doctor, I am an industrialist, I am an industrialist’s son, I am a social worker and so on. Besides, I may not be unemployed much longer. My father, though only a Superintendent in the Ministry of Commerce, intends to pull strings, as he says, and get me a job. In the meantime I have persuaded him to buy me a season-ticket on the Indian Railways which I could still buy at a student’s concession even though I was not a student anymore.

In Tuticorin though, which is Tuti-Korhi in Tamil and probably means ‘Do work and eat’, I abandoned the railway and travelled with a bus-load of Ayappans, whose bus I accidentally got onto and from where I did not get off until Nagercoil, where a great mara-mari took place between two politicians. Or, maybe, it was a fight between two actors’ clubs. It was not clear. The Ayappans talked a lot but they also were not clear. The mara-mari amused everybody. And in the mara-mari I was left behind. So, sitting on the rock, waiting for the sun I thought of three things. First: there was a little too much of mara-mari on the land that lay before me. Second: it was not easy to know who was fighting whom. Third: everything stood for something else. A politician could be an actor. An actor could be a politician. You did not know. All this I thought about sitting on the rock waiting for the sunrise. My body felt cold. I got up and did ten push-ups. This made my legs warm.

Next I thought of a ball point pen that I had lost somewhere. I had been very upset at the time because it was a good pen and it was not mine. It belonged to my sister’s husband who is in the Customs. He had received it from a London Indian whom he had allowed to bring in some dutiable goods without paying duty. He had given it to me for my examinations but I had yet to return it. And now, of course, it was lost. What face was I going to show to my sister’s husband? I had told the whole story to the Ayappan who sat next to me. He had helped me search the bus inside out but you cannot create a ball point out of air, by which I mean that you cannot find a thing if it is not there. So we gave up the search and the Ayappan said God has taken it away because your sister’s husband should not have taken it in the first place. I said he had not taken it, it had been gifted to him. The Ayappan said it came to the same thing. He was very polite and he shook his head every time he talked and clicked his tongue in a strange way and his teeth were very white in his mouth. I looked to the east. There was no sign of the sun. I looked to the west which was stupid because the sun cannot rise in the west. Then I did ten more push-ups. Now the rest of me became nice and warm too and I sat down again and thought of the Ayappans.

And what I thought was that it was nice to see so many young men looking for God together. It was, in a way, like going out for a hockey match, of which I played a good many in college. Maybe I should have stayed on with them even though I did not know what it was all about. I was not sure whether an unemployed graduate engineer should look for God instead of looking for a job. Because, first, I did not understand their language. Second, I had really come to see the sunrise at Kanyakumari. And also the sunset. I could not go home without seeing them. Third, where was God?

There was still no sign of the sun.

There was more light though. I could see farther along the beach to the left and to the right. There were palm trees and sand and a thin line of surf. And, I thought, all this length of beach is just a dot on the map. Maybe not even a dot. And if all this was only a dot then this country, Bharat, which I had just left, like the great Swami, must be a very big country. I thought then of another thing, which was that this very big country was really full of very small people. I was still thinking of those actors or politicians or fan clubs that had been fighting in Nagercoil and who had made me lose my way and my bus and my friend of the ball point.

I thought a bit about my Ayappan. And what I thought was that it was strange that people still went about wearing black lungis and a vow. I had asked the Ayappan why he did it. He said he had faith. I said I did not have faith. He said my hope of seeing the sun rise over Kanyakumari was a sort of a faith. He said it was good to see the sun rise over the country where one was going to work and marry and so on. All the time the Ayappan talked he shook his head and clicked his tongue and seemed very excited. I had not looked at it that way but, sitting on the rock, I thought the Ayappan had a point. Why else had I come?

Here was another matter. Some people had faith and some people did not have faith. And both were having trouble because those who had faith were often let down and those who did not have faith got mixed up. Faith was like the angle at which you set your telescope if you wanted to see a star. I mean, you had to know the angle. You could take my case. I was sitting on the rock but I did not have an angle. Of course my classification was unemployed graduate engineer and I had to get a job but that did not give me an angle.

This made me think of a teacher in my old school who pronounced the angel in Abu-bin-Adam as angle and was not laughed at. But when I got to the university I found that very good professors were laughed at. So, as they say, even in my short life the times had changed.

Things, I thought, had changed even though I was so young. And, maybe, it was because things had changed that I was unemployed because sometime back, when I started college, let us say, it had not seemed that I would be no more than an unemployed graduate engineer.

This gave me another idea which was that, as my grandfather says, maybe everything is connected with everything else. He had been a guard, a railway guard, and he says he used to have a lot of time to think things through riding up and down the trains. And all his thinking during all those years had only convinced him that everything was connected with everything else. The world is one big clock, he says. And maybe it happened that once young people started laughing at decent teachers the world stopped giving those young people jobs. It was possible. Such things seem possible in a dawn like this. But it made me a little gloomy, although there is nothing gloomy in all these thoughts, as anybody can see.

Then I thought of a very big minister who had said only the other day that there was no reason for gloom. He had said it near Kanyakumari. He was speaking to people who had come from a great drought. I thought the minister must know what he was talking about and, maybe, there was no reason for gloom and I should cheer up. But I felt bad all the same. I thought maybe I felt the way I did because there was no sun yet and that I would brighten up when the sun came out and that I should sit quietly and wait for the sun to rise.

I did not have my watch but it seemed there would be another half-hour before the sun rose. After the sunrise I planned to swim right back. I could have returned by steamer, too, but the Swami had swum back and anything else would have been cowardice. My grandfather, the railway guard, after reading the papers one morning, had made a modification to his theory. Everything was, of course, connected with everything else, he said but running through a length of fifty beads, was cowardice. I had not understood it then and I did not understand it standing on the rock; but not swimming back, I knew, would have been cowardice. So, after the sunrise, I was going to swim back. Come hail or sunshine.

My grandfather, the railway guard, had some notions in common with the Ayappan, like his notion about the ball point, although my grandfather did not believe in God and things like that. He said you could either believe in God or you could believe in the railway engine; you could not believe in both. I did not know which one I believed in. Ever since I had been an unemployed graduate engineer my mother had made me go to the temple every Tuesday with sweets and ask for a job after the arati, which was not fair because you can’t ask people for things so shamelessly even if they are God. Of course, I had not got a job, which made me doubt both the railway engine and God, which is not good because too much doubting is too much strain.

At this point, someone at my elbow said, ‘It is not going to be.’ I was startled. It was a thin dark man. What struck me about him was his hair which was totally grey. Absolutely, I mean one hundred per cent like my grandfather’s. It looked very odd because his face was quite young. He seemed to have come out of the interior of the temple.

‘It is not going to be,’ he said again. He did not look at me but stared out at the sea.

‘What is not going to be?’

‘What you are expecting, what else.’

‘And what am I expecting?’

‘What everyone expects when they come to this rock at this time.’

‘You mean the sunrise.’

‘Yes, the sunrise. Other things too.’

‘We shall see.’

‘What will you see? How old are you?’

‘Twenty-one.’

‘I am sixty-three. How will you see what I have not seen in thrice as many years.’

‘Every book says you can see the sun rise at Kanyakumari.’

‘Books say many things.’

‘They can’t all be wrong.’

‘Books are the biggest liars. You will find out.’

He got up then and went off carrying a broom which I had not noticed until then.

To tell the truth, I did not like his interference, or him for that matter. It was like when my grandfather started speaking without anyone asking him to. It was quite a bit like that.

It is very bright now. The sirens should go off any minute. With the sirens, my guide book said, the sun would begin to rise. I thought of the day ahead and all that I would do. Now that I had lost the Ayappan I was quite alone but there were plenty of things that even a lone man could do. Then, beyond the day, was my life. No doubt, for the moment, I had been classified as an unemployed graduate engineer but that did not need always to be the case. I was only twenty-one, after all. My father was forty-nine and my grandfather was eighty-nine. So there were plenty of years in my life yet and I thought of all the things that I would do irrespective of gloomy things that people like my grandfather and that man with the broom kept saying. The books had to be right. Nobody had any business trying to be cleverer than the books.

Just then the sirens went off. I turned sharply to the east but there was no sign of the sun. A cloud hung on the horizon except that it was not a cloud. Nor was it a fog or mist. It was just a haze, a curtain through which you could not see. I thought maybe I was in the wrong place. So, I ran up along the rock to the back of the temple. But there was no sun there either. Just the grey haze, a blanket. You could see nothing, not even a glow.

‘I told you so.’

It was the man with the broom. He was sweeping the yard. ‘The sun never rises the way it is meant to,’ he said.

‘But the sirens have gone off.’

‘Anyone can make the sirens go off. They are always putting in bigger and better sirens but what does the sun care for their sirens. And now you had better hurry if you want to catch the boat back.’

I stood in the boat waiting for it to start. I had planned to swim back but the sun not rising had knocked something out of me and I decided to take the boat. My hands felt numb. I noticed I was clutching the railing too hard. I was nervous. Something had unnerved me which was silly, of course, especially because I could not put my finger on it. I let go of the railing, crossed my arms over my bare chest and put my foot on a board.

People in the movies are always standing like that and it gave me reassurance. But just then the boat heaved and I nearly fell on my face. I grabbed the rails once again.

There was no sign of the sun. The boat moved towards the mainland. ‘That is the tip of India,’ a father explained to his son, ‘just as you have it in the map.’ And beyond the tip I thought was India itself. But you could see nothing of it. There was a haze all over. You couldn’t see very far because the sun had yet to rise. I wished I had not missed that bus with my Ayappan friend. I missed him. And it was true you could set up sirens and write things in books any way you wanted. They didn’t mean very much. Books and sirens didn’t make the sun rise. Just as the man had said.

Arun Joshi

(Arun Joshi was an acclaimed novelist, and also the recipient of the prestigious Sahitya Academy Award, and used his gift to express the many experiences of his own personal quest.)