All of us are confronted with various types of fears, though their nature may vary from person to person. Very often we do not even try to overcome them, or if we try we find it very difficult.

Once when the Mother was taking a class for children, she was asked:

Why does one often behave like a coward? Why is it so difficult to overcome fear?

The Mother’s answer to the children takes up some interesting examples of how some trainers handle wild animals, and gives interesting insight on how we can conquer our fears.

Tamas, Rajas and Fear

I think that one is cowardly because one is very tamasic and fears having to make an effort. In order not to be cowardly, one must make an effort, begin by an effort, and afterwards it becomes very interesting. But the best thing is to make the effort to overcome this kind of fright out of oneself. Instead of facing the thing, one recoils, runs away, turns one’s back and runs away. For the initial effort is difficult. And so, what prevents you from making an effort is the inert, ignorant nature.

As soon as you enter the rajasic nature, you like effort. And at least the one advantage of rajasic people is that they are courageous, whereas tamasic people are cowards. It is the fear of effort which makes one cowardly. For once you have started, once you have taken the decision and begun the effort, you are interested. It is exactly the same thing which is the cause of some not liking to learn their lessons, not wanting to listen to the teacher; it is tamasic, it is to be asleep, it avoids the effort which must be made in order to catch the thing and then grasp it and keep it. It is half-somnolence. So it is the same thing physically, it is a somnolence of the being, an inertia.

I have known people who were physically very courageous, and were very, very cowardly morally, because men are made of different parts. Their physical being can be active and courageous and their moral being cowardly. I have known the opposite also: I have known people who were inwardly very courageous and externally they were terrible cowards. But these have at least the advantage of having an inner will, and even when they tremble they compel themselves.

Different Types of Courage

Once I was asked a question, a psychological question. It was put to me by a man who used to deal in wild animals. He had a menagerie, and he used to buy wild animals everywhere, in all countries where they are caught, in order to sell them again on the European market. He was an Austrian, I think. He had come to Paris, and he said to me, “I have to deal with two kinds of tamers. I would like to know very much which of the two is more courageous. There are those who love animals very much, they love them so much that they enter the cage without the least idea that it could prove dangerous, as a friend enters a friend’s house, and they make them work, teach them how to do things, make them work without the slightest fear. I knew some who did not even have a whip in their hands; they went in and spoke with such friendliness to their animals that all went off well. This did not prevent their being eaten up one day. But still— this is one kind. The other sort are those who are so afraid before entering, that they tremble, you know, they become sick from that, usually. But they make an effort, they make a considerable moral effort, and without showing any fear they enter and make the animals work.”

Then he told me, “I have heard two opinions: some say that it is much more courageous to overcome fear than not to have any fear…. Here’s the problem. So which of the two is truly courageous?”

There is perhaps a third kind, which is truly courageous, still more courageous than either of the two. It is the one who is perfectly aware of the danger, who knows very well that one can’t trust these animals. The day they are in a particularly excited state they can very well jump on you treacherously. But that’s all the same to them. They go there for the joy of the work to be done, without questioning whether there will be an accident or not and in full quietude of mind, with all the necessary force and required consciousness in the body. This indeed was the case of that man himself. He had so terrific a will that without a whip, simply by the persistence of his will, he made them do all that he wanted. But he knew very well that it was a dangerous profession. He had no illusions about it.

The Tamer and the Cat

He told me that he had learnt this work with a cat—a cat! He was a man who, apart from his work as a trader in wild animals, was an artist. He loved to draw, loved painting, and he had a cat in his studio. And it was in this way that he began becoming interested in animals. This cat was an extremely independent one, and had no sense of obedience. Well, he wanted to make a portrait of his cat. He put it on a chair and went to sit down at his easel. Frrr… the cat ran away. So he went to look for it, took it back, put it back on the chair without even raising his voice, without scolding it, without saying anything to it, without hurting it of course or striking it. He took it up and put it back on the chair. Now, the cat became more and more clever. In the studio in some nooks there were canvasses, canvasses on which one paints, which were hidden and piled on one another, behind, in the corners. So the cat went and sat there behind them. It knew that its master would take some time to bring out all those canvasses and catch it; the man, quietly, took them out one by one, caught the cat and put it back in its place.

He told me that once from sunrise to sunset he did this without stopping. He did not eat, the cat did not eat, he did that the whole day through; at the end of the day it was conquered. When its master put it on the chair it remained there and from that time onwards it never again tried to run away. Then he told himself, “Why not try the same thing with the bigger animals?” He tried and succeeded.

Of course he couldn’t take a lion in this way and put it on a chair, no, but he wanted to get them to make movements— silly ones, indeed, such as are made in circuses: putting their forefeet on a stool, or sitting down with all four paws together on a very small place, all kinds of stupid things, but still that’s the fashion, that’s what one likes to show; or perhaps to stand up like a dog on the hind legs; or even to roar—when a finger is held up before it, it begins to roar—you see, things like that, altogether stupid. It would be much better to let the animals go round freely, that would be much more interesting. However, as I said, that’s the fashion.

But he managed this without any whipping, he never had a pistol in his pocket, and he went in there completely conscious that one day when they were not satisfied they could give him the decisive blow. But he did it quietly and with the same patience as with the cat. And when he delivered his animals—he gave his animals to the circuses, you see, to the tamers—they were wonderful.

The Vibration of Fear

Of course, those animals—all animals—feel it if one is afraid, even if one doesn’t show it. They feel it extraordinarily, with an instinct which human beings don’t have. They feel that you are afraid, your body produces a vibration which arouses an extremely unpleasant sensation in them. If they are strong animals this makes them furious; if they are weak animals, this gives them a panic. But if you have no fear at all, you see, if you go with an absolute trustfulness, a great trust, if you go in a friendly way to them, you will see that they have no fear; they are not afraid, they do not fear you and don’t detest you; also, they are very trusting.

It is not to encourage you to enter the cages of all the lions you go to see, but still it is like that. When you meet a barking dog, if you are afraid, it will bite you, if you aren’t, it will go away. But you must really not be afraid, not only appear unafraid, because it is not the appearance but the vibration that counts.

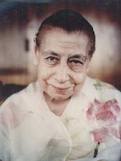

The Mother