While one may derive love and joy from human contact, it is just as common to come into conflict and experience friction, at times from the very same relationship that once made us happy. Does quarrelling or antagonism hold a place in the life of a sadhak? Sri Aurobindo doesn’t think so.

People are drawn together or one is drawn to another by a certain feeling of affinity, of agreement or of attraction between some part of one’s own nature and some part of the other’s nature. At first this only is felt; one sees all that is good or pleasant to one in the other’s nature and even attributes, perhaps, qualities to him that are not there or not so much there as one thinks. But with closer acquaintance other parts of the nature are felt with which one is not in affinity — perhaps there is a clash of ideas or opposition of feelings or conflict of two egos.

If there is a strong love or friendship of a lasting character, then one may overcome these difficulties of contact and arrive at a harmonising or accommodation; but very often this is not there or the disagreement is so acute as to counteract the tendency of accommodation or else the ego gets so hurt as to recoil. Then it is quite possible for one to begin to see too much and exaggerate the faults of the other or to attribute things to him of a bad or unpleasant character that are not there. The whole view can change, the good feeling change into ill-feeling, alienation, even enmity or antipathy. This is always happening in human life. The opposite also happens, but less easily — i.e. the change from ill-feeling to good feeling, from opposition to harmony. But of course ill-opinion or ill-feeling towards a person need not arise from this cause alone. It happens from many causes, instinctive dislike, jealousy, conflicting interests, etc. One must try to look calmly on others, not overstress either virtues or defects, without ill-feeling or misunderstanding or injustice, with a calm mind and vision.

*

Well, I have said already that quarrels, cuttings are not a part of sadhana: the clashes and friction you speak of are, just as in the outside world, rubbings of the vital ego. Antagonisms, antipathies, dislikes, quarrellings can no more be proclaimed as part of sadhana than sex-impulses or acts can be part of sadhana. Harmony, goodwill, forbearance, equanimity are necessary ideals in the relation of sadhak with sadhak. One is not bound to mix, but if one keeps to oneself, it should be for reasons of sadhana, not out of other motives: moreover, it should be without any sense of superiority or contempt for others…. If somebody finds that association with another for any reason raises undesirable vital feelings in him or her—he or she can certainly withdraw from that association as a matter of prudence until he or she gets over the weakness. But ostentation of avoidance or public cuttings are not included in the necessity and betray feelings that equally ought to be overcome.

*

If you want to have knowledge or see all as brothers or have peace, you must think less of yourself, your desires, feelings, people’s treatment of you, and think more of the Divine — living for the Divine, not for yourself.

*

Quarrels and clashes are a proof of the absence of the yogic poise and those who seriously wish to do yoga must learn to grow out of these things. It is easy enough not to clash when there is no cause for strife or dispute or quarrel; it is when there is cause and the other side is impossible and unreasonable that one gets the opportunity of rising above one’s vital nature.

*

As for your question, it is a sentimental part of the vital nature that quarrels with people and refuses to speak to them and it is the same part in a reaction against that mood that wants to speak and get the relation. So long as there is either of these movements the other also is possible. It is only when you get rid of this sentimentalism and turn all your purified feelings towards the Divine, that these fluctuations disappear and a calm goodwill to all takes their place.

*

There are two attitudes that a sadhak can have: either a quiet equality to all regardless of their friendliness or hostility or a general goodwill.

*

Do not dwell much on the defects of others. It is not helpful. Keep always quiet and peace in the attitude.

*

Men are always more able to criticise sharply the work of others and tell them how to do things or what not to do than skilful to avoid the same mistakes themselves. Often indeed one sees easily in others faults which are there in oneself but which one fails to see. These and other defects such as the last you mention are common to human nature and few escape them. The human mind is not really conscious of itself — that is why in yoga one has always to look and see what is in oneself and become more and more conscious.

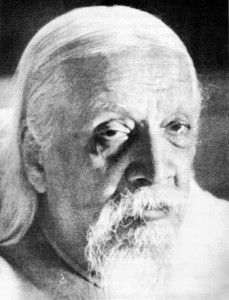

Sri Aurobindo