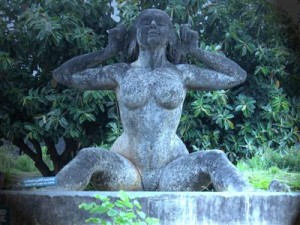

Not long ago, the colossal nude sculpture, christened Yakshi that dominated the Malampuzha Gardens near Palaghat in Kerala caused a law and order problem. A few vagrants suddenly ran amok, like the Biblical pigs on Lake Galilee when possessed by a “legion” (of spirits), and since there was no lake at hand for them to get drowned and disappear, they pounced upon a passing lady who had a narrow escape.

To leave the sculpture in peace at the risk of its occasionally wreaking havoc on others’ peace, or to exile it to a safe annexe in a museum was the question with the authorities concerned.

But my questions are: how did the sculptor get the idea that the Yakshi, a member of a clan of demigods, more affluent than the other clans of the species such as Vidyadharas, Apsaras, Gundharvas and Kinnaras, could not afford to drape herself in some celestial linen and jewellery? Why did the sculptor assign her to the desolation of an acre of grass in a park whereas according to the Agni Purana, a Yakshi’s rightful place, when presented visually, is the wall of a temple?

Erotic sculpture is no novelty in India, their range extending from Konarak and Khajuraho to the frescoes of even Ajanta and Ellora. If they never caused any law and order problem, why should a newly modelled Yakshi? Is it because, its name notwithstanding, it was nothing more than a gifted sculptor’s fancy for a voluptuous creation, a certain arbitrariness leading to its appearing in a park, isolated from a relevant context? What is the feeling its maker expected her to arouse in the beholders? Devotion? Serenity? Could any sensible artist be under the illusion that the pronounced sensuousness of the figure could be offset simply by its awe-inspiring name or its overwhelming volume?

Even if honest answers to these questions were to indicate that the sculpture, despite the talent involved in its making, could not guarantee against some titillation in an average beholder, a titillation to neutralise which there was neither a touch of the sublime in it nor the reverential atmosphere of a shrine around it, it could most probably continue to sit harmless in a different milieu. But today obscenity and vulgarity have pervaded our climate. Even though wise commercial establishments are doing their best, engaging sophisticated minds and media, to bill out undiluted vulgarity as avant-garde culture, all they have achieved is a state of explosiveness in our social life and collective behaviour.

The cutthroat consumerism is a culture devoted to stimulating so many hungers and its survival depends on keeping the hungers alive, for, to satisfy them would prove self-defeating to it. We may be proud of a great cultural heritage, incredible spiritual achievements and mature pragmatism, but our collective cultural status is dubious at the moment. In our social culture, we swing between inertia and easy excitement. We are eager to hitch our wagon to a star, but are most uncertain in regard to our priorities amidst the stars. If today the star of patriotism inspires us, tomorrow it is regionalism or language or caste or worse. We are willing to be swept by any violent wind of passion let loose by the little evil geniuses among us.

I fear that while art has been used as a means to introduce elegance in several spheres of our life – and in this devil of consumerism must be given its due – anarchy has invaded the realm of art-appreciation or, to put it differently, in the appreciation of art proper. The victim is an average art-lover like this reviewer. Two factors are responsible for this: art, dislodged from its environment and often bereft of the right context not only fails to evoke the expected response, but also arouses wrong response. Secondly, despite commendable innovations and fascinating experiments and a high degree of perfection in form, modern art is lacking in the quality of inspiration – inspiration in its creative and somewhat occult sense – not in the sense of motivation.

In that well-known art gallery of Paris, Galerie Louise Leiris, there is a queer object of art: the bronze cast of the seat and handlebars of an old bicycle arranged in a manner to assume the semblance of a bull’s head and indeed, it is so captioned. This is a ‘creation’ of Pablo Picasso.

For long I have wondered as to why I should be obliged to look upon it as art. A History of Art by H. W. Jonson (Professor of Fine Arts, New York University), a standard work on art and its values, tells me: “While we feel a certain jolt when we first recognise the ingredients of this visual pun, we also sense that it was a stroke of genius to put them together in this unique way, and we cannot very well deny that it is a work of art.”

I stand even more intrigued. Was this a stroke of genius? We are neither concerned with the original maker of the bicycle seat and the handlebars nor with the question whether he could be called a genius or not. But can a man who merely arranged the two things in a different manner (in the process squeezing out of them their utility too) and made them resemble something else, be a genius? Hundreds of combinations are made by children while playing with different things. Do we call then geniuses? The other day a friend and I simultaneously saw the silhouette of Konarak in a distant hut in combination with a banyan tree behind it, from a certain angle. We did not compliment each other as geniuses!

The question that naturally arises is, could this object, “The Bull’s Head”, have been taken note of had it been put together by you or I? Could I have escaped the reputation of a lunatic had I carried it to an art exhibition and claimed a prominent patch of wall to hang it?

Here, it is relevant to be reminded of Picasso’s famous confession (1965):

“The people no longer seek consolation or inspiration in art. But the refined people, the rich, the idlers, seek the new, the extraordinary, the original, the extravagant, the scandalous. And myself, since the epoch of Cubism, have contented these people with all the many bizarre things that have come into my head. And the less they understood it, the more they admired it.”

I believe that it is the childish or the whimsical or the fanciful in Picasso, and not the artist, which contrived “The Bull’s head”. Picasso is a genius. Hence this had to be the product of a genius. And once we concentrated on it, it was our own genius that became active in discovering God’s genius inherent everywhere. Once our eyes are tuned in keeping with our mind’s expectations and suggestions, we can detect wonders in practically everything!

I believe that it is this greater law, which is at work in some, or perhaps many people marvelling at Picasso’s “The Bull’s Head” and not the artistic excellence of the object. There is a mystic hidden in every individual. You need only an occasion to awaken it. In this case Picasso is the occasion — Picasso the symbol, not Picasso the artist.

However, we have to differentiate between our capacity to see marvels in any or everything — “To see a world in a grain of sand and Heaven in a wild Flower,/ Hold infinity in the palm of your hand, and Eternity in an hour” (Blake), and our capacity to appreciate man-made art expressing the creative inspiration which is at work behind the making of the frescoes of Ajanta or a Mona Lisa. This again has to be differentiated from crafts and objects fulfilling our utilitarian needs, though they have in them elements of art. In fact, art has conquered domains once outside it with the growth of affluence, art education and technological revolution. That in this process art has lost something of its dignity and sanctity is a different matter and perhaps a paradox to be put up with.

Now, when on one hand we separate art from the splendours of God inherent in everything and on the other hand from crafts and objects with mere elements of art, our rational mind can very well look for a working definition of art. A clear-cut definition can rarely convey the spirit of the total thing. We should better try to understand the phenomenon rather than define it.

To struggle for existence may be a primary instinct with all creatures and naturally, with man too. But man extends his struggle to make his existence something more than mere survival; he ennobles it with ideals and beauty. But his efforts at adorning himself with such qualities are only signs of a basic trait hidden in him. That is the evolutionary nisus, the urge inherent in him to exceed himself. “An eternal perfection is moulding us in its own image”, says Sri Aurobindo. Man can never remain satisfied with what he is; he must expand in every direction – through music he will like to sound the hitherto unknown chords of his awareness; through dance he must wake up to the ecstasy of a rhythm loftier than the pattern of his daily chores and through art he must discover and project not only his vision of the grand and the perfect, but also the moods, poise and tranquillity of his inner or greater self.

Self-discovery, not only by the artist, but also by the beholder of art, is a part of the process. Splendid natural sunrises and sunsets are taking place every day of the year. We rarely stand and stare at them. But a painting of the sunrise or the sunset will attract us. Pictures of a flower, an animal, a man, the sea, though much less wonderful than their real models, will always look marvellous to us. We take the real things for granted, for they, after all, are made by God or Nature who or which is omnipotent. But that a human being could create something even remotely similar, is surprising, for man knows how limited he is!

This element of surprise may be there in case of any other invention by man, but the kind of self-discovery involved in the process of creating or enjoying art is comprised not only of the element of wonder but also of the joy and serenity of knowing oneself better which in the long run contributes to our knowing better the supreme Spirit pervading everything. It holds especially good in regard to Indian art. “For the Indian mind form does not exist except as a creation of the spirit and draws all its meaning and value from the spirit. Every line, arrangement of mass, colour, shape, posture, every physical suggestion, however many, crowded, opulent they may be, is first and last a suggestion, a hint, very often a symbol which is in its main function a support for a spiritual emotion, idea, image that again goes beyond itself to the less definable, but more powerfully sensible reality of the spirit which has excited these movements in the aesthetic mind and passed through them into significant shapes.” (Sri Aurobindo: The Foundation of Indian Culture)

Perhaps it is time the artist, the painter, the sculptor stopped for a moment and asked himself a few questions concerning the nature and quality of his inspiration. This apparently worn-out cliché – inspiration – has an uncanny capacity for returning and asserting itself and revealing hitherto unknown splendours if the artist sought it as an honest devotee of art.

A Postscript without comment:

A chill of embarrassment swept the world of art-critics in Britain in February 1993. The s selected and displayed a picture entitled Rhythm of the Trees, in the watercolour category, for its “colour balance, composition and technical skill,” for their prestigious exhibition of outstanding contemporary paintings.

Alas, it was soon found out that the painter was a toddler who had dabbed a brush in colours kept ready by his uncle and had used it on a canvas at hand and had abandoned the enterprise probably at the sight of a toy or a toffee. The phenomenon of prodigy may be a recognized fact, but in this case neither the four-year-old nor its parents claimed the ‘art’ to be the product of any freakish genius. In fact the ‘artist’s mother said that she had sent the painting ‘as a joke’ to amuse the trained eyes, never with the idea of seeing it again!

Manoj Das

(Manoj Das is an internationally known creative writer. He is the recipient of India’s national recognition, the Sahitya Akademi Award and the nation’s most prestigious literary award, the Saraswati Samman. As a social commentator, his columns in India’s national dailies like The Times of India, The Hindustan Times, The Hindu and The Statesman, revealing the deeper truth and the untraced aspects behind current issues, have been highly appreciated.)