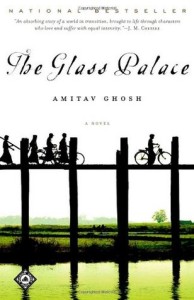

Amitav Ghosh’s The Glass Palace is an epic novel that traces the political, social and cultural transformation of British colonies India, Malaya and especially Burma in the period 1890’s to 1990’s. The story begins in Burma with the dethroning of King Thebaw and his exile to India, to spend rest of his life in the little known western coastal town of Rathnagiri. The end of the novel is again in Burma, now Myanmar, with the most promising leader, Aung San Suu Kyi in house arrest in her own country.

The period of the story is not an ordinary one; those were the hundred years that has made the world what it is now. Two big world wars, one great economic depression in between, a crucial time for British imperialism with the struggle of Independence in the peak of its effort, also this was the period when the colonies gained independence to create a new world order signifying the post second world war era, with the advent of America as the new land of opportunities. Also this was the period that saw the most of human passion for innovation with leap of advancements in science and technology.

The Glass Palace’s story showcases all these points in the history of those decades. The story revolves around a few families whose lives become intertwined by the circumstances that make the history. The family of the King Thebaw, his wife Queen Supalayat, their two daughters and the royal entourage that leaves Mandalay for exile, a young Indian boat helper Rajkumar and his descendents, teak Contractor Saya John , his son Matthew and his family, Uma Dey, wife and later the widow of the Collector of Rathnagiri, who eventually becomes one of the pioneers of Indian Freedom struggle.

Raj Kumar enters Mandalay because of a boat accident, just when the British have decided to do away with King Thebaw and monarchy in Burma for the sake of the monopoly on teak. Amitav Ghosh comes down heavily on the weakness and delusions of the Royal families of the sub continent and their inability to provide any shield against the manipulation, manpower and the aggressiveness of the Imperialistic Britain.

With Mandalay becoming a British headquarter as soon as the King goes in exile, Rajkumar gets initiated in to the teak trade as an apprentice under the soft spoken, intelligent businessman, Saya John. The growth of Rajkumar from a young inquisitive boy to a young man with a bright future in teak business in Rangoon is narrated alternatively with the decline of the moral and financial status of the Royal household in their captivity in the seaside town of Rathnagiri. This alternative narration culminates after a twenty years, with the marriage of Rajkumar to Dolly, the only servant girl who had been staying with the Royal household since they had left Burma.

Then the story moves on to Rangoon and focuses on the political and economic development of the early 1900’s. By the time the First World War starts, Rajkumar, Saya John and his son Matthew, have hit the pot of gold in the flourishing timber trade and their intuitive investment in the rubber plantations. The growth and prosperity of the timber businessmen in Burma and rubber plantation owners in Malaya is sketched neatly along with the rapid cultural and social changes these places undergo due to massive movement of people from other countries, particularly southern India, to work as “coolies” in the rubber plantations.

But the Second World War coupled with the economic downturn of the Depression just before that and the more complex and ideologically incoherent Indian Freedom movement has a more brutal surprise in store for the region and the families involved in the story. The majority of the second generation perishes in the war and related confusions, the first generation characters are left with a third generation infant, as a new world-order begins with India and rest of the colonies gaining independence and America raising as the super power.

The story takes place in Mandalay, Rathnagiri, Rangoon, Malaya and Calcutta. Amitav Ghosh makes a lucid presentation of the cultural and economic transformation that the countries involved undergo, fuelled mainly by the prolonged British rule. At the end of the story, one can see that India and Malaya have been able to cross the tide with the political and economic stability in the offing for the decades that followed. But Burma has a different story to tell. A jewel in the crown of Asia, a treasure house of natural wealth has been reduced to poverty and instability. Ghosh points the role of imperialists, their greed and manipulative expertise in turning the land of riches into one of confusion and chaos. This contrast is brought about in the first and last chapters. Rajkumar is mesmerized by the colors, aroma and the dazzle of the city of Mandalay as he walks through the city for the first time. He even notes that the country is literate, more accommodating and devoid of caste and religious distinction. He ends up spending most part of his life in cosmopolitan Rangoon. Then in the final chapter, Rajkumar’s granddaughter Jaya comes to Rangoon in the late 1990’s to search for her uncle and Rajkumar’s second son, Dina. The poverty ridden empty streets of Rangoon as she sees them, provides a sharp contrast to the one her grandfather fell in love with a century ago.

Amitav Ghosh’s brilliant prose writing is evident in his ability to make the readers go back in the time machine and go into the households of ordinary citizens and their families to feel the enormity of change the period brought on their lives. The novel spans a time of hundred years and three generations. Naturally, a large number of characters are involved, who are linked to one another through friendship, loyalty and love. Ghosh has sketched the characters such that each of them face the circumstances presented to them, in tune with the characterizations; they do not smudge beyond their intended portrayals; there is no surprising twist and turns in the character’s handling of any situations. This wide range of characters with varied nationalities, customs, religions also depict clearly their social and political leanings. The diversity of the characterization provide ample chance for different views and the writer banks on this to provide an absorbing set of exchanges and arguments to highlight the concepts of freedom, slavery, loyalty, etc.,

While dealing with larger political implications of the issues, Ghosh has also weaved into the storyline certain subtle, intricate power games that comes between: a Queen and her slave girl, an exiled queen and an Indian Collector serving the British, an eager to be westernized husband and a self righteous wife, a nervous parent and an attention seeking child, an Indian solider and a British Officer, an Indian Army Officer serving British army and an Indian sepoy in the army, the immigrant coolies and the plantation owners – the novel is laden with these interesting multi layered relationships.

The writer presents us with some beautiful analogies.

“The slope ahead was scored with the shadows of thousands of trunks, all exactly parallel, like scratches scored by a machine. It was like wilderness, but not yet. Dolly had visited Huay Zedi several times and had come to love the electric stillness of the jungle. But this was neither city nor farm nor forest: there was something eerie about this uniformity; about the fact that sameness could be imposed upon a landscape of such natural exuberance.”(199)

…

There’s a law, there’s order, everything is well run. Looking at it, you would think everything is tame, domesticated, that all parts have been fitted carefully together. But it’s when you try to make the whole machine work that you discover that every bit of it is fighting back. It has nothing to do with me or with rights or wrongs: I could make this the best run little kingdom in the world and it would still fight back”

These exchanges are about the rubber trees. This is the same kind of work that is involved in colonization, subjugating a country, stamping the unique cultural and social ethos of the land , claiming to provide a better civilization and a better way of life.

Amitav Ghosh brings out a brilliant analogy in the decay of a country’s wealth and moral health in the description of the ruins in the Malayan forest.

“He beat a path through the undergrowth and found himself confronted with yet another ruin, built of the same materials as the two chandis- laterite- but of a different design…. He climbed gingerly up the mossy blocks and at the apex he found a massive square stone, with a rectangular opening carved in the centre. Looking down, he found a puddle of rain water trapped inside…. What was the opening for? Had it once been a base for a monumental structure- some gigantic smiling monolith? It didn’t matter: It was just a hole now, colonized by a family of tiny green frogs.”(334)

The gradual growth of the forest into an abandoned city or a temple is described so delicately along with the systematic and purposeful colonization by the imperialists that changes the very fabric of the society for posterity.

Ghosh also points out that the colonization and subjugation for centuries together has resulted in a drastic change in the social and cultural phenomena of the continent itself and hence the results of the British rule cannot be summarized just as it has been done for decades down in the history books: bring social reforms, literacy, technological advancements. These just happened accidentally. This was not the prime object of the colonization; that was only business and power, the ingredients of building an Empire.

What would have been these countries – India, Burma, Malaya – without British Imperialism? What has been made of these cultures after the British left, leaving behind irreparable scars of social and economic patterns? Did India achieve the freedom that was fought for? What has become of Burma, now Myanmar that still struggles to establish a progressive democratic government? The Imperialists created a delusion that they would reform the countries, grant freedom to the people from the monarchy. Was doing away with the monarchies and bringing them under the colonial power a way to freedom?

Writing a book on the colonial era, decades after the British left the countries, might be an interesting process to look at these issues with a detached attitude, to make a critical judgment of the native emperors and the colonizers, and also to understand why we are what we are and why all our current political and social problems date back to this era. How much of our problems of today can be hinged to yesterday’s catastrophes?

“To use the past to justify the present is bad enough – but it is just as bad to use the present to justify the past. And you can be sure that there are plenty of people to do that too: it’s just we don’t have to put up with them.” (537)

– Smitha Vasudevan