By his effort, his vigilance, his discipline and self mastery, the intelligent man should create for himself an island which no flood can submerge.

The fools, devoid of intelligence, give themselves up to negligence. The true sage guards vigilance as his most precious treasure.

Do not let yourself fall into carelessness, nor into the pleasures of the senses. He who is vigilant and given to meditation acquires a great happiness.

The intelligent man who by his vigilance has dispelled negligence, mounts to the heights of wisdom, whence he looks upon the many afflicted as one on a mountain looks down upon the people of the plain.

Vigilant among those who are negligent, perfectly awake among those who sleep, the intelligent man advances like a rapid steed leaving behind a weary horse.

Vigilance is admired. Negligence is reproved. By vigilance, Indra became the highest among the gods.

The Bhikkhu who delights in vigilance and who shuns negligence advances like a fire consuming all bonds, both small and great.

The Bhikkhu who takes pleasure in vigilance and who shuns negligence can no longer fall. He draws near to Nirvana. (Dhammapada)

I have read out to you the whole chapter because it seemed to me that it is the totality of the verses that creates an atmosphere and that they are meant to be taken all together and not each one separately. But I strongly recommend to you not to take the words used here in their usual literal sense.

Thus, for example, I am quite convinced that the original thought did not mean that you are to be vigilant in order that you may be admired and that you must not be negligent in order not to be reproved. Besides, the example given proves it, for certainly it was not for the sake of gaining admiration that Indra, the chief of the overmental gods in the Hindu tradition, practised vigilance. It is a very childish way of saying things. Yet, if you take these verses all together, they have by their repetition and insistence, a power that evokes the thing which seeks expression; it puts you in relation with a psychological attitude which is very useful and has a very considerable effect, if you follow this discipline.

The last two verses particularly are very evocative. The Bhikkhu moves forward like a burning flame of aspiration and he shuns negligence.

Negligence truly means the relaxation of the will which makes one forget his goal and pass his time in doing all kinds of things which, far from contributing towards the goal to be attained, stop you on the path and often turn you away from it. Therefore the flame of aspiration makes the Bhikkhu shun negligence. Every moment he remembers that time is relatively short, that one must not waste it on the way, one must go quickly, as quickly as possible, without losing a moment. And one who is vigilant, who does not waste his time, sees his bonds falling, every one, great and small; all his difficulties vanish, because of his vigilance; and if he persists in his attitude, finding in it entire satisfaction, it happens after a time that the happiness he feels in being vigilant becomes so strong that he would soon feel very unhappy if he were to lose this vigilance.

It is a fact that when one has made an effort not to lose time on the way, any time lost becomes a suffering and one can find no pleasure of any kind in it. And once you are in that state, once this effort for progress and transformation becomes the most important thing in your life, the thing to which you give constant thought, then indeed you are on the way towards the eternal existence, the truth of your being.

Certainly there is a moment in the course of the inner growth when far from having to make an effort to concentrate, to become absorbed in the contemplation and the seeking of the truth and its best expression-what the Buddhists call meditation-you feel, on the contrary, a kind of relief, ease, rest, joy, and to have to come out of that in order to deal with things that are not essential, everything that may seem like a waste of time, becomes terribly painful. External activities get reduced to what is absolutely necessary, to those that are done as service to the Divine. All that is futile, useless, precisely those things which seem like a waste of time and effort, all that, far from giving the least satisfaction, creates a kind of discomfort and fatigue; you feel happy only when you are concentrated on your goal.

Then you are really on the way.

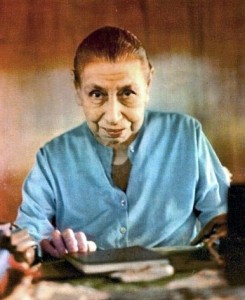

The Mother